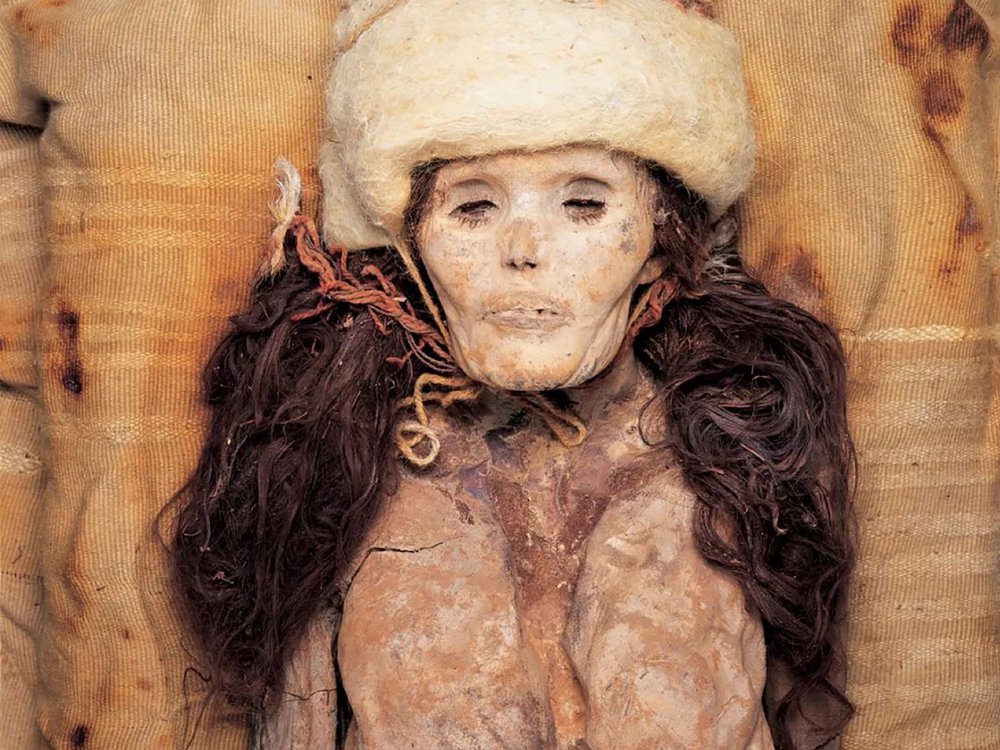

Researchers say eerily well-preserved Bronze Age mummies uncovered in far west China’s Taklamakan Desert decades ago were not travelers from the West, as previously theorized, but part of an indigenous group descended from an ancient Ice Age Asian population.

In the 1990s, roughly 300 mummies dating from between 2,000 B.C. to 200 A.D. were uncovered in tombs in the Tarim Basin in China’s autonomous Xinjiang Uyghur region.

The reddish brown hair, unusual clothing, and expansive diet of the Tarim Basin mummies led experts to believe they were migrants from southern Russia or other regions west of China

The reddish brown hair, unusual clothing, and expansive diet of the Tarim Basin mummies led experts to believe they were migrants from southern Russia or other regions west of China

The region’s dry atmosphere and freezing winters preserved the remains, most notably that of ‘the Beauty of Xiaohe,’ whose facial features, clothing, hair and even eyelashes are discernible. (Her name is derived from the site where the tombs were discovered.)

The so-called ‘Western’ features of the Tarim Basin mummies — including red and light-brown hair — coupled with their unusual clothing and diet, led many experts to believe they were migrants from the Black Sea region of southern Russia.

That theory was bolstered by the fact that they were buried in boat coffins in the middle of a barren desert.

Pictured: An aerial view of the Xiaohe cemetery, where the mummies were found

To get a clearer idea of their origins, an international team of researchers analyzed genomic data from 13 of the oldest known mummies, who date from between 2100 and 1700 B.C.

They compared it with DNA samples from five individuals who lived further north in the Dzungarian Basin about 5,000 years ago, making them the oldest known human remains in the region.

The scientists found the Tarim Basin mummies were not newcomers at all, but direct descendants of Ancient North Eurasians (ANE), a group that largely disappeared by the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,550 years ago.

Only traces of ANE genetics still survive in the Holocene, our current geological epoch: Native Americans and indigenous Siberians retain the highest known proportions, about 40 percent.

This Bronze Age community likely experienced ‘an extreme and prolonged genetic bottleneck prior to settling the Tarim Basin,’ according to a statement from the Max Planck Insтιтute for Evolutionary Anthropology, which co-sponsored in the research.

‘Archaeogeneticists have long searched for Holocene ANE populations in order to better understand the genetic history of Inner Eurasia,’ senior author Choongwon Jeong, a biologist at Seoul National University, said in the release.

‘We have found one in the most unexpected place,’ Choongwon added.

The people of the Tarim Basin were genetically isolated but ‘culturally cosmopolitan,’ according to senior author Christina Warinner, a Harvard anthropologist.

‘They seem to have openly embraced new ideas and technologies from their herder and farmer neighbors, while also developing unique cultural elements shared by no other groups,’ Warinner told CNN.

They wore felted and woven woolen clothing, used medicinal plants like ephedra from Central Asia; and even ate kefir cheese, which originated in the North Caucasus.

Senior author Yinquiu Cui, a professor in the School of Life Sciences at Jilin University, in Changchun, China, said discovering the origin of the Tarim Basin mummies has had ‘a transformative effect on our understanding of the region.’

Yinquiu said he hopes to analyze ancient human genomes from other eras ‘to gain a deeper understanding of the human migration history in the Eurasian steppes.’

The group’s findings were published in the journal Nature.

In 2011, China temporarily barred the mummies from being exhibited after they had been touring North America for months.

Officials gave no reason why the exhibition was halted but there was speculation that it may be linked to the mummy’s Western appearance and Chinese sensitivities about what that implied for the region’s history.