While digging along a dried-up riverbed in northern Florida, a team of paleontologists and volunteers from the Florida Museum of Natural History unearthed a collection of bones from an elephant species that lived in the region during the Miocene Epoch, which spanned a period from 23 million to 5.33 million years ago.

These elephant forerunners, known as gomphotheres, went extinct long ago. But approximately six million years ago they populated what is now northern Florida in impressive numbers. For whatever reason, it seems the bones of many gomphotheres ended up at the exact same spot along the banks of an ancient river near the modern-day city of Montbrook, forming what could be labeled an “elephant graveyard.”

Issac Magallanes with a juvenile gomphothere tusk. ( Florida Museum )

The fossilized skeletal remains discovered by the Florida Museum of Natural History researchers included animals that died hundreds of years apart in some cases. Yet their bones were found in the same place, suggesting that some unique natural phenomenon must have been responsible for this intergenerational accumulation.

Fortunately, several of the ancient elephant skeletons recovered were virtually intact, including one skeleton from a full-grown adult. This gave paleontologists a unique opportunity to study the anatomy of a huge and fascinating creature that once freely roamed North America just like modern elephants wander across Africa today.

The adult gomphothere skull (foreground, tusk capped in white plaster) was separated from the main body (background, covered in plaster) prior to its preservation. (Kristen Grace/ Florida Museum )

The explorations of the prehistoric riverbed outside Montbrook began in early 2022, as scientists and volunteers descended on the region with the express intent of finding ancient fossils left behind by animals that lived there in the incredibly distant past.

Between five and 5.5 million years ago, during the late Miocene and early Pliocene, the now-dead river was a thriving freshwater ecosystem populated by a dizzying variety of fish, amphibians, reptiles and water birds. Large mammals like the gomphothere would have come there to drink water as well.

Almost immediately after their excavations began, the participants in the appropriately named Montbrook Fossil Dig began unearthing gomphothere bones. As the excavations continued, one of the volunteers on the project, a retired chemistry teacher from Montbrook named Dean Warner, came upon the fossilized remains of an unusually large animal.

Eventually a complete adult gomphothere skeleton was recovered at that spot, and as the digging continued the scientists and volunteers found other smaller intact skeletons, from a total of seven juvenile animals in all.

Left; Volunteer with a gomphothere jaw. Right; Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager, Richard Hulbert, adding glue to the fossils of the ‘elephant bone bed’. ( Florida Museum )

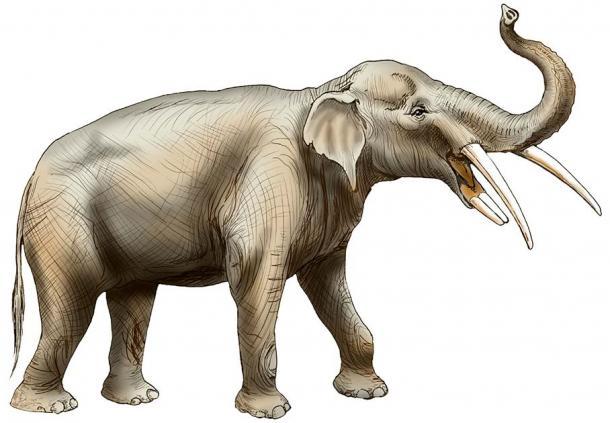

While the adult gomphothere was large compared to other members of the species found at the ancient riverbed, it was comparable in size to a modern adult African elephant. The five-to-six-million-year-old fully-grown gomphothere was approximately eight feet (2.4 meters) tall, while its skull and tusks were slightly more than nine feet (2.7 meters) long from front to back. These dimensions make it the largest gomphothere skeleton ever recovered anywhere.

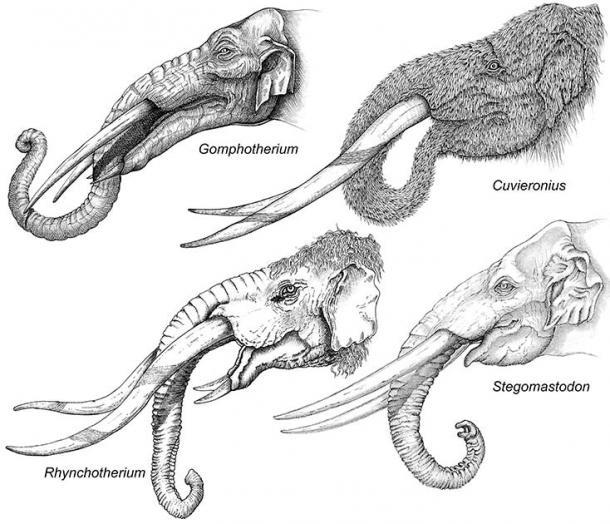

Gomphotheres can be coarsely identified by their tusks, which have unique shapes, orientations and banding patterns that differ by group. (Illustrations by Pedro Toledo/ Florida Museum )

Scientists deny that elephants are capable of intentionally choosing a place to die. But this doesn’t necessarily debunk the elephant graveyard concept. It could be that old or sick elephants prefer to lie down and rest close to familiar fresh water sources, and if that was happening in the area around Montbrook millions of years ago it would explain how so many gomphotheres passed away in the same location. This would make such a location a de facto elephant graveyard, even if the elephants themselves didn’t think of it in that way.

As of now, the paleontologists responsible for this amazing discovery are going with a different theory. They speculate that the intact adult gomphothere drowned at the spot where his skeleton was found, but that the dead bodies of the other ancient animals had been swept into the river during floods and deposited at that spot because it was located at a bend in the river. Over time the skeletons began to pile up, making it seem as if they’d come there intentionally to die.

Whatever the truth is about its origin, there is no doubt that the discovery of this prehistoric elephant graveyard represents a stroke of tremendously good fortune.

Gomphotheres were among the most diverse proboscideans and spread to nearly every continent during their 20-million-year reign. (Merald Clark/ Florida Museum )

During the Miocene Epoch , these relatives of the modern elephant occupied open savannahs that could be found in Africa, Eurasia and the Americas. But grasslands began to replace many of these savannahs in North America, and increasingly intense competition for precious resources led to the extinction of the gomphotheres approximately 1.6 million years ago.

Many unanswered questions about the lives and lifestyles of this long-extinct species remain. But the Florida Museum of Natural History researchers are excited about how much they will be able to learn from studying the supremely well-preserved gomphothere fossils found along the ancient riverbed in Florida.

Ultimately, the fossilized bones from the intact adult animal will be pieced back together and put on public display at the Museum, right next to the skeletons of mammoths and mastodons that are already part of the Museum’s extensive fossil collection.

Top image: Researchers and volunteers with the Florida Museum of Natural History have discovered the ancient remains of several gomphotheres (elephant ancestors) at a fossil site in North Florida. Source: Kristen Grace/ Florida Museum

By Nathan Falde