The Angels’ Mike Trout became a superstar during one Iowa summer: ‘A time we’ll never forget’Stephen J. NesbittJun 3, 2022

When Don and Robin Grawe agreed to be a host family for the Single-A Cedar Rapids Kernels in 2010, they weren’t sure what they were signing up for. They’d done it as a favor to Lanny Peterson, the Kernels housing coordinator, who’d brought up the idea at church one Sunday. “Oh,” Robin replied. “That might be fun!” Now that their sons were grown, the Grawes had extra space in their empty nest, a four-bedroom home on a hillside in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

ADVERTISEMENT

The team flew in one evening in the first week of April 2010 and bused to Veteran Memorial Stadium. Don and Robin were given the names of two 18-year-olds they’d never heard of. They wandered the concourse, weaving past bags and baseball detritus until running into a lanky, laidback Californian and an energetic Jersey kid who introduced themselves as Tyler and Mike.

Tyler Skaggs. Mike Trout.

That night, as Trout and Skaggs unpacked in the walk-out basement they’d share, Don went into his home office and Googled the players’ names. Both were first-round picks with million-dollar signing bonuses the previous year.

“I was like, oh, these kids must be pretty good,” Don recalls now, 12 years later, then laughs at his Larry David-esque understatement.

This was back before Trout was the best player on the planet, before he was the highest-paid man in baseball history, before he was a surefire first-ballot Hall of Famer, before he had three MVPs and four second-place finishes, before he was a husband and a father, before he was the much-criticized commissioner of a high-roller fantasy football league, before he was 30 and having one of his best seasons yet — slashing .292/.396/.616 with 13 homers to fuel the Angels’ playoff hopes.

Back then, Trout was anonymous to the average fan. That changed in Cedar Rapids. His three months with the Kernels were when the baseball world realized Mike Trout was, well, Mike Trout.

He showed cartoonish speed. He mashed baseballs. He stole homers. He rocketed to the top of prospect lists as talent evaluators discovered that the high schooler they had scouted on soggy fields in frigid northeast weather was, in fact, a superstar in the making.

The Athletic spoke with Trout’s former teammates, coaches, hosts and others in the Angels organization to tell the story of the Iowa summer when Trout strode into the spotlight.

No one remembers it better than Don and Robin. Trout and Skaggs still have a special hold on their hearts. They watched as the two boys who crushed junk food in their basement became big leaguers; celebrated with them on their wedding days; mourned with their families when Skaggs died of an opioid overdose in 2019. To Don and Robin, the two of them will always be Mike and Tyler, the 18-year-olds cheerfully bouncing up the stairs each morning.

“It’s a time we’ll never forget,” Don says.

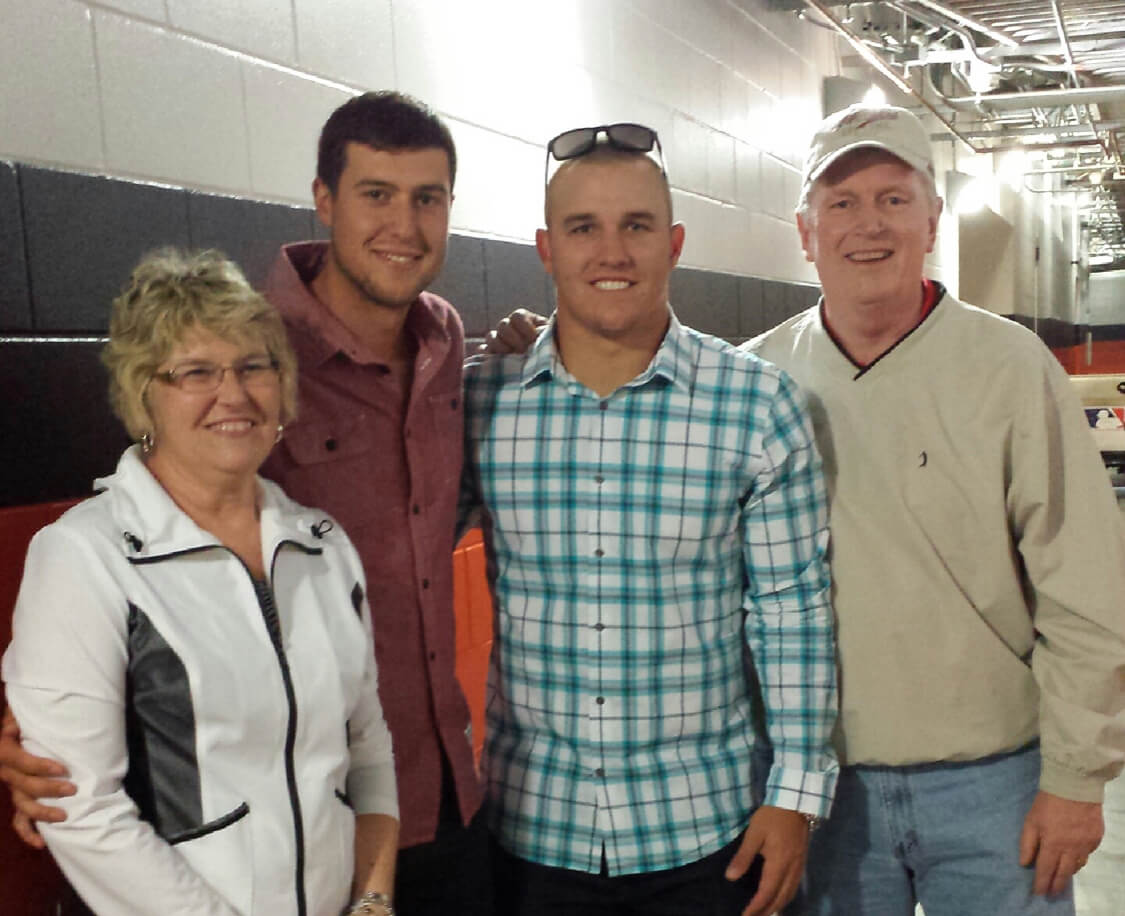

Robin and Don Grawe with Tyler Skaggs (center left) and Mike Trout in 2017 (Courtesy of the Grawes)

Trout had been in Cedar Rapids once before, but only briefly. In September 2009, three months after graduating from Millville Senior High School in New Jersey, Trout was called up to join the Kernels for the Midwest League playoffs after batting .360 as a 17-year-old in rookie ball.

“Has anyone ever said you look like a young Mickey Mantle?” longtime Kernels general manager Jack Roeder asked after picking up Trout at the airport.

“Yeah,” Trout said, with a smile, “I’ve heard that.”

Trout was the youngest player on the Kernels roster by two years. He appeared in only one postseason game — as a pinch-runner — because manager Bill Moisello wanted to reward the players who had carried Cedar Rapids to a 78-60 regular-season record. With Trout on the bench, the Kernels lost in the semifinals. “I was dumb enough to not even start him,” Moisello says.

For that first stint in Cedar Rapids, Trout and a teammate stayed with Bill and Janis Quinby. When Trout arrived in his black 2009 Toyota Tacoma — his signing-bonus splurge — Bill backed the couple’s car out of the garage and told Trout to park inside. “Oh no, Mr. Quinby, my truck can sit in the driveway,” Trout said. The neighborhood was safe, but Bill wouldn’t have forgiven himself if someone stole Trout’s truck. Bill peeked through the window of the Tacoma and saw the backseat was littered with Old Hickory baseball bats and Nike gloves and spikes Trout had gotten from his endorsements. Bill asked how expensive all of that equipment was. Trout guessed $3,000. That was that. The truck went into the garage.

Bill, a retired Big Ten and NFL official now in his 90s, recalls how Janis would make the players breakfast each morning, and they’d help her tidy up the kitchen afterward. “We had the best relationship you could ever have with two young men that you had never met before,” Bill says. Janis died four years ago, and it’s still meaningful to him how kind those players were to her.

Before heading home to New Jersey, Trout thanked the Quinbys by taking them to dinner in Cedar Rapids. He gave Bill a mitt and a pair of spikes. The shoes didn’t fit, so Bill gave those back, but he kept the glove for his grandson.

Jeremy Berg, a reliever on the 2010 Kernels, remembers hearing that of the two high-school outfielders the Angels had drafted back-to-back in the first round in 2009 — Randal Grichuk 24th, Trout 25th — one was a power guy and the other a speed guy. Sizing them up in spring training, Berg assumed Trout, who had 25 pounds on Grichuk, was the power guy.

It took Berg only one workout to realize he was wrong. Supposedly, Trout was the speed guy. He really was both. Trout was one of the fastest players in the organization — so speedy that then-Angels GM Tony Reagins says he believed Trout would steal 50 bases per season in the majors — and he homered five times in the last week of spring training, flexing the muscle he’d added that winter.

“Someone asked, ‘Dude, what did you do?’” infielder Jon Karcich remembers. “Mike said, ‘I just crushed steak and Pepsi all offseason long.’”

The Pepsi-and-steak pop in spring training made it more surprising when the season started in Cedar Rapids and Trout’s power surge immediately ceased. That’s why everyone’s first memory of Trout’s 2010 season in Cedar Rapids is of Trout pounding the ball into the ground and busting it down the baseline. Roeder recalls watching from the press box as Trout beat out a routine grounder. He asked the broadcast producer, “Can you replay that? I missed something.”

Roeder hadn’t missed a thing. The shortstop charged, fielded the ball cleanly and fired to first. Trout just outran it. Eleven of his first 13 hits that season were infield singles. He was out of sorts at the plate yet batting .313. “You’re like, this guy’s never getting into a slump with that speed,” catcher Jose Jimenez says.

On another April day at the Kernels ballpark, former Angels GM Bill Stoneman told Roeder, “Trout’s the fastest player I’ve seen home to first base,” before adding a caveat: “I never saw Mantle at his prime run home to first.” Moisello remembers a scout clocking Trout at 3.89 seconds to first — an outrageous time for a right-handed hitter — on another infield single.

“You hear him when he runs,” Moisello says.

“It’s like the ground was shaking,” adds outfielder Jeremy Cruz.

Still, Kernels hitting coach Brenton Del Chiaro thought Trout’s all-speed, no-slug start might be eating at him, so he sat Trout down one afternoon in late April to ask how he was feeling. “Deli, I’m not seeing the ball great,” Trout told him, as upbeat as ever. “But I will.”

There wasn’t much open late at night in Cedar Rapids, especially for a teenager, so after Kernels night games Trout could usually be found at one of two places.

The first was the Buffalo Wild Wings two miles from the ballpark. There’d be 10 players circling tables in the restaurant drinking beer and watching games on TV. Too young to order alcohol, Trout settled for an assortment of appetizers (“He would just order so much,” pitcher Patrick Corbin recalls. “He’d order three or four appetizers, eat all that, and order an entree or two”) and soda refills. “I’ve never seen someone drink so much Pepsi and still be such a freakish athlete,” Cruz says. “When you’re 18 years old, you can drink four Pepsis every night and still go to bed.”

The other postgame hangout was the Grawes’ basement. Don and Robin would hear the Tacoma rumbling down the hill toward their house, and Trout and Skaggs would walk in the front door with a rotisserie chicken they’d picked up at the grocery store. Then they’d crash on the basement couch to eat and play video games — just two kids living the minor-league dream.

“Nutrition was not high on either of their lists as 18-year-olds,” Don says, laughing. “My grandkids are that age now, and it’s not high on theirs either.”

This dichotomy defined Trout’s time in Cedar Rapids. On the field, he conjured comparisons to all-time greats. Off of it, he was a kid far from home for the first time, finding his way in the world, with a messy truck, an insatiable appetite and otherworldly athleticism. (During a road series in Peoria, Ill., the Kernels held an impromptu dunk contest at a public gym. Teammates recall Trout throwing down alley-oops, reverses, windmills and attempting 360s.)

Trout was surrounded by top-end talent on a Kernels roster that featured 11 future major leaguers — including Jean Segura, Garrett Richards, Grichuk, Corbin and Skaggs — and the clubhouse meshed well. Trout was fun-loving and unassuming, always looking for competition in the weight room and eager to invite every teammate to host-family barbecues and Buffalo Wild Wings. “Everyone loved being around him,” says infielder Kevin Ramos. Others say Trout was respectful to coaches and hosts; friendly to everyone from the groundskeepers to the bat boy; quick to volunteer to spend a morning with Kernels broadcaster John Rodgers reading to 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren at local schools; and even quicker to help pull the tarp on the field in a downpour.

One rainy afternoon, Trout climbed the dugout steps at Veteran Memorial Stadium as Roeder and his son Jesse, the team’s turf manager, worked along the muddy first-base line. A noted weather junkie, Trout would talk through the weather radar with Jesse whenever there was a chance of rain in the forecast. He didn’t root for rainouts, but studying the storms was a thrill.

“Whaddya think, boss?” Trout asked that day. “Are we gonna play tonight?”

“I don’t know,” Roeder replied. “What do you think?”

Trout walked over to first base.

“He takes a lead like he’s going to steal second,” Roeder recalls, “then he takes off and falls flat in the mud — face first. He gets up and goes, ‘It looks ready to me.’”

Mike Trout at the 2010 Futures Game (Jeff Gross / Getty Images)

Mike Trout at the 2010 Futures Game (Jeff Gross / Getty Images)

It’s not that Trout flipped some switch in Cedar Rapids and suddenly was destined for stardom. That much was already inevitable. But it wasn’t until he was raking for the Kernels, destroying Single-A pitching in his first full season of pro ball like he was still facing high-school heaters, that the industry fully realized his greatness. Prior to the 2010 season, Keith Law, now with The Athletic, ranked Trout as the No. 48 prospect in baseball — no slouch, but not a sure thing — while Baseball America had him considerably lower at No. 85.

On May 2, 2010, Trout crushed his first home run of the season, a no-doubter off the bat launched over the left-field wall at Veteran Memorial Stadium. He had tapped into his power, and line drives again started flying all across the outfield. Over the next month, Trout batted .378/.468/.639 with six homers, 16 stolen bases and an invitation to the Midwest League all-star game.

“There were so many of those oh-my-God, holy-shit plays that it almost became routine,” reliever C.J. Bressoud says.

Law refreshed his rankings in May 2010 and elevated Trout to No. 14. The baseball world was on notice.

“You’d go into Cedar Rapids, and the buzz would be there when you walked through the door,” Reagins says. “(Trout) was doing something impressive every night.”

Trout rarely struck out, but when he did he’d smile and give the pitcher a nod. More often than not, Trout got him back the next time up. Del Chiaro, the hitting coach, remembers making only one tweak to Trout’s swing. The barrel of the bat was getting too far behind Trout’s head, making his swing longer. Trout watched video, worked on the change one day in the batting cages, and it was fixed. “That’s when it kind of hit you: This is special,” Del Chiaro says.

“He shines when you watch him,” Cruz says, “but when you actually play with the guy, you realize he’s a different animal.”

Moisello had managed plenty of good prospects before — from Sean Casey and Todd Helton to Austin Jackson and Aaron Boone — but he raved to evaluators about Trout’s maturity (“He acts like he’s Derek Jeter at 18 years old”) and his talent (“This is the best player I’ve ever seen”). Moisello would then tell the evaluators not to repeat those words to reporters. It’s not that Moisello was afraid to say them; he just didn’t want to put extra pressure on Trout.

One day that summer, Moisello told then-Yankees hitting coach Kevin Long about Trout’s latest feat. He’d hit a ball into the left-field corner at Veteran Memorial Stadium and turned it into a triple. “Nobody does that,” Moisello says.

Two years later, in Trout’s rookie season, he did the same thing against the Yankees. Long texted Moisello: I thought you were full of baloney, but he did it.

No matter how late he’d been up the previous night, Trout would be out the door by 8 a.m. to go hit some golf balls. The Kernels gave each player free passes to local courses, and on days when Corbin and Richards weren’t starting they’d play an early round with Trout and Berg.

Trout had just picked up the game as a post-high school hobby. He compensated for his inexperience with power. “He’d crush the ball,” Corbin says. “Hit it a lot harder and farther than I ever could.” Trout and Berg shot in the 80s. Corbin and Richards tried to keep up. But while Trout hit the ball a mile, he also hit it far too high in the air, so the others rooted for strong winds to knock his round off course. They soon discovered he was a swing perfectionist in golf, too.

“He’d hit a bad shot and be like, ‘Hey, guys, hold on a second,’” Berg recalls. “He’d look up a YouTube video on a golf swing, drop a few balls, practice his swing and then hit another one.”

By now, the lasting images of Trout’s golf game are his off-the-balcony trick shot and his swing at an Albert Pujols fundraising event at TopGolf in 2021. In the latter, Trout squares up a tee shot and sends it on a line toward the back netting, disappearing in an instant into the darkness as Trout’s teammates lose their minds. That’s the same swing teammates contended with in Cedar Rapids, but even better now. Karcich remembers Trout lining up an iron at a Kernels charity golf event in 2010: “The dude took a swing and frickin’ piped this ball so far, so straight. It was like, is there anything he can’t do?” That shot made it onto a local news segment.

Don Grawe, by his own account, isn’t a great golfer, but he enjoys it enough to hang photos in his office of the most interesting courses he’s played. Trout equated the photos with Don being very good, so whenever the two of them talked about playing a round together Trout would say, “When I’m good enough, we’ll play.”

Twelve years later, Trout still owes him a round. “From what I know of his golf game now,” Don says, “yeah, he’s more than good enough.”

One day in Cedar Rapids, Trout threw out a pair of worn-out Nike spikes. After he walked out of the clubhouse, teammates started arguing over who would keep the shoes as a souvenir.

“Those things weren’t going to go in the trash can,” Berg says, laughing. “I just remember being like, ‘Guys, this is our teammate. This is kind of weird.’”

They all knew Trout wouldn’t be in town much longer. Rodgers, the broadcaster, saved the scorebook and stats from Trout’s three months with the Kernels, and he later gifted Moisello a copy of the scorebook page from Trout’s last game with the Kernels. As June turned to July, Law slid Trout to No. 3 in his midseason rankings, writing, “Oh, just call him up already. The way he’s going, he probably could handle it.” (Trout debuted a year later, on July 8, 2011.)

Trout was selected for the Futures Game at Angel Stadium on July 11, 2010 — a perfect opportunity for the Angels to show off Trout at his future home ballpark. Trout, the youngest player on either roster, was prepared in every way but one: He’d forgotten dress pants.

Traveling to Anaheim from a road series in Burlington, Iowa, Trout traded a broken bat to Cruz for a pair of khakis. Trout planned to give the pants back when he returned to Cedar Rapids for the second half of the season. Neither of them knew he’d already played his last game for the Kernels. Cruz likes to think Trout still has those khakis somewhere; the broken bat is in storage. “It ain’t going anywhere,” Cruz says. “It’s one of his original Old Hickorys.”

The morning of the Futures Game in Anaheim, Trout was featured on the cover of Baseball America and named their new No. 2 prospect. He pinch-ran in the first inning after the No. 1 prospect, Phillies outfielder Domonic Brown, injured his hamstring. Trout proceeded to do exactly what he’d done in Cedar Rapids. He legged out an infield single, stretched a single into a double, and used his speed to cause two errors. Back in Cedar Rapids, his coaches watched on TV and couldn’t help but laugh. They’d seen it all before.

“That game is when everyone was like, ‘Whoa, what is this?’” Del Chiaro says. “The guy is built like Brian Urlacher but has a world-class s𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁set.”

Afterward, Reagins told Trout he was headed to Class High-A Rancho Cucamonga. The Angels had seen enough in Cedar Rapids. In 81 games with the Kernels, Trout batted .362/.454/526 with six homers and almost as many stolen bases (45) as walks (46) and strikeouts (52). Trout flew back to Iowa to gather his things from the Grawes basement. He walked through the front door of their home and greeted Don with a hug and a huge grin.

“I’m moving up,” Trout said.

It was still dark the next morning when Trout loaded his bags into the Grawe family car to head to the airport. Don woke Robin, and she came downstairs to say goodbye. As Don drove Trout to the airport, they made plans to ship Trout’s bats to California and to see each other at spring training. And then Trout was gone.

“To be honest, I’ve probably never seen him happier than that day,” Don says. “He was itching to get out and be promoted. You knew it was coming.”

Mike Trout signing autographs in Anaheim (Christian Petersen / Getty Images)

Mike Trout signing autographs in Anaheim (Christian Petersen / Getty Images)

Today, as Trout continues his legendary career in Anaheim, his former Cedar Rapids teammates still carry mementos and memories from their short time together in the minor leagues. Cruz has the broken bat. Someone has the spikes. They point at the TV screen during Angels games and say, Yeah, he was doing stuff like that when he was 18. They talk about him scoring from first on a single, or from second on a sacrifice fly.

“It seems like I’m always pointing to a Mike Trout story,” says Berg, who now coaches at Lone Peak High School in Highland, Utah, “just to explain, ‘This is why this guy is so good. He plays the game the right way, and then he also has the talent on top of it. And that’s why we’re talking about him right now.’”

The Grawes have remained close with the Trout and Skaggs families. They all were together for the last time at Skaggs’ wedding in December 2018, and it was Trout’s mother, Debbie, who phoned the Grawes seven months later when Skaggs was found dead in a suburban Dallas hotel room. An autopsy concluded Skaggs had fentanyl, oxycodone and alcohol in his system; a jury earlier this year found former Angels communications director Eric Kay guilty of providing the drugs that 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁ed Skaggs.

Two days after Skaggs’ death, Trout spoke through tears about the teammate he’d known since they were drafted by the Angels. “Lost a teammate, lost a friend, a brother,” Trout said.

Watching Trout that day, Don and Robin thought back to the day they first met Trout and Skaggs and brought them to their Cedar Rapids home. The laidback Californian. The energetic Jersey kid. The two of them were proof that oil and water do mix, Robin says. Don adds, “Those guys were inseparable. Even now, we can’t talk about one without the other.”

In 2016, Del Chiaro was a hitting instructor at Angels spring training. The day Trout reported to camp, he walked into the clubhouse and lifted Del Chiaro off the ground. “Deli! What’s going on?!” Del Chiaro hadn’t talked to Trout in a few years, but he was the same fun-loving kid he remembered — just not nearly as anonymous anymore. After a round of swings in the batting cages, Trout said he’d pay $500 if Del Chiaro put on catching gear and stood at the other end of the cages: “Let me just whack baseballs at you!” Del Chiaro declined that tempting offer, though it would have made for a great story.

Toward the end of camp that spring, Del Chiaro asked Trout if he’d sign a baseball for his son Beckett, who was 6 months old at the time. Trout said he would. After the workout that day, Del Chiaro found a signed bat in his locker:

To Beckett:I’ll See You In The Show.Mike Trout

Now, that bat is carefully wrapped in a bat case at the back of a closet in the Del Chiaro home. Beckett is 7, and Trout is one of his favorite players. Del Chiaro hasn’t given his son the bat yet. It’s sacred, he says. But he has told Beckett all about coaching Trout, about their time together in Iowa, about how he’s one of the greatest to ever play the game. And when he gives Beckett that bat, Del Chiaro will tell him Trout’s the type of guy who doesn’t forget an old friend.

“He picked up like we were back in Cedar Rapids,” Del Chiaro says.